DEFINING TRADITIONS 1969 -1996. Living and working with holography

INTRODUCTION

The theme of this session of the Symposium made me feel a little uneasy. I had a problem seeing myself as a traditionalist, rather than an innovator. I still feel that to earn the label "creative" artists need to be original, and at the time I began making holograms I felt that to originate a new field was to do my job properly as an artist.

My art work began in a traditional way, as a painter. By around 1964 my paintings, for want of a better word, could be described as "optical symbolic". I was using systems of various kinds, optical illusions, colour and so on, to modulate the picture plane so that it no longer looked flat. But in particular it was my use of the graphic interference pattern or moiré that drew my attention to holography when I read about it in a newspaper in 1967.

The description in the newspaper, of the ways in which the interference pattern of light could do what I was already attempting to do in paint, led me to see a potential medium in holography. Paint had various restrictions. So I negotiated a Fellowship at this very University at Nottingham, where this Symposium is taking place. Here I began to experiment, making my first test plates in 1968. The old lab that I used is still here, on campus, like a time-travel machine. It is impossible to describe my feelings at re-discovering the same spaces that I worked in then. The gallery area where the current symposium exhibition is being held is like a palimpsest of my first exhibition, which was held in the same place. Sculptor Jerry Pethick, the inventor of the sand table, saw my first exhibition here in 1969. He brought news of Lloyd Cross and Editions Inc. I also knew about Bruce Nauman's show at Knoedler, but we did not know that artists Harriet Casdin-Silver and Carl Frederick Reutersward were also working with holography at that time.

EARLY WORK (1)

What I found with my early work in holography was that I became medium-led. I had to experiment. There was a whole new field out there, and it was not possible to continue with old preoccupations. It was necessary to start again. So I decided to treat each hologram as a prototype for future possible directions.

One of my early holograms uses the light itself

as the subject. The hyperreal aspects of holography still draw

people to it, but I think that the most basic, primitive, pre-verbal,

reason for artists is the fact that we are working with light.

The light is primary. Having worked with it for a lifetime, for

a multiplicity of purposes, I feel that the underlying reason

why I am making holograms and not paintings is because they are

a purer way of connecting with those early, pre-verbal memories

that are experiences of light. With holography we can take that

primary experience of light, and form images. For me in the early

days this meant making art-historical comments, for example,

or making everyday things appear to float through each other.

The still lives took the hologram out of the lab into everyday

life, using the optical table as a domestic table. Hot Air made

the first use of what I called non-holograms, which were eventually

re-named shadowgrams. This piece is in the collection of the

Australian National Gallery as an "avant-garde classic",

which is a lovely contradiction in terms.

One of my early holograms uses the light itself

as the subject. The hyperreal aspects of holography still draw

people to it, but I think that the most basic, primitive, pre-verbal,

reason for artists is the fact that we are working with light.

The light is primary. Having worked with it for a lifetime, for

a multiplicity of purposes, I feel that the underlying reason

why I am making holograms and not paintings is because they are

a purer way of connecting with those early, pre-verbal memories

that are experiences of light. With holography we can take that

primary experience of light, and form images. For me in the early

days this meant making art-historical comments, for example,

or making everyday things appear to float through each other.

The still lives took the hologram out of the lab into everyday

life, using the optical table as a domestic table. Hot Air made

the first use of what I called non-holograms, which were eventually

re-named shadowgrams. This piece is in the collection of the

Australian National Gallery as an "avant-garde classic",

which is a lovely contradiction in terms.

I made what I thought of as a movie hologram in 1970. It was a triple exposure hologram with separated exposures, so that as you swivelled the plate one exposure would fade and the next would come up. I particularly loved the paradoxes in holography. A series of holograms of a loaf of bread taken over a number of days showed the bread looking dramatically rotten when it was actually fresh, and looking fresh when it had become rock-hard and solid enough to record. Clock, Mirror, Hypercube was a pseudoscopic hologram, time reversed, so that you see the back before you see the front of the image. You are like Alice, on the other side of the mirror. These were all laser viewable holograms, and they were all didactic, in that they were intended to be prototypes and to exclude personal experiences.

Another art fellowship followed at Strathclyde University in Scotland in 1971. Here I lived on baked beans, was granted half the cost of a laser from the Leverhulme Trust, and built my own lab in the Department of Architecture. At this time an article about my work was published in the journal Leonardo, and also in a book, Kinetic Art (2), and my work became known internationally. Britain's information services had issued official photographs of my work, and the show at the Lisson Gallery in London in 1970 had generated a great deal of publicity, but the Leonardo writing gave other artists the idea that they could make their own holograms. It was still quite a radical idea. For years I found that some scientists did not actually believe that I was making them myself.

I remember being visited by Anait during my time in Scotland. My fellowship lasted until 1973, and by then the content of my work was beginning to change. Bird in Box 1973 was the first piece I made that had an emotional, personal undercurrent. Only recently have I been able to admit that although officially it was a hologram of a complete closed surface, unofficially it was about my feelings as a scapegoated female artist in the architecture department, a boxed-in "bird". I was beginning to use holography for sociological comment, as in Brave New World and Third World. An interactive piece, Jigsaw, was a game in which players could discover for themselves that a hologram was an indivisible whole. It was quite an extraordinary experience to see the "many-in-one" manifest itself under your fingers as you played this game. Because the holograms were laser-lit I displayed them in darkened conditions, and in my final exhibition at Strathclyde housed them in a cardboard collapsible space quite appropriate for showing holograms, since holography has been described by Bohm as "an enfolded order".

AUSTRALIA

After leaving Scotland there were some

radical life experiences in the form of two very small babies,

and a move to another country, Australia (3). By 1978 I was able

to resume work where I had left off, following the same pattern

of art fellowships, this time at the Australian National University.

Any decision about setting up on my own, was postponed. I preferred

to work in an academic setting, pooling my equipment with scientists.

More reflection tests

resulted in a process piece which was deliberately intended to

deteriorate over time. I sometimes wonder what it looks like

now, in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

I made a piece against the commercialism of Xmas for an exhibition

of cards by artists, and carried out a full-colour collaboration,

Rainbow Rainbow, with scientists at the CSIRO Sydney. I also

made a reflection version of Jigsaw, which could be played outside

in the sun. By 1979 my work had became more cross -cultural and

about the land I found myself living in. Solar Markers is an

example (4). Mixed media works hybridised the holograms with

drawings and paintings, or the holograms themselves were scratched

and drawn into. Lattice, and the Unclear World and Greenhouse

series of holograms are examples of this. I found that the mixture

of media gave me increased scope for yet more socio-political

comment, and at the same time made my work easier to appreciate

for those used to more traditional media.

More reflection tests

resulted in a process piece which was deliberately intended to

deteriorate over time. I sometimes wonder what it looks like

now, in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

I made a piece against the commercialism of Xmas for an exhibition

of cards by artists, and carried out a full-colour collaboration,

Rainbow Rainbow, with scientists at the CSIRO Sydney. I also

made a reflection version of Jigsaw, which could be played outside

in the sun. By 1979 my work had became more cross -cultural and

about the land I found myself living in. Solar Markers is an

example (4). Mixed media works hybridised the holograms with

drawings and paintings, or the holograms themselves were scratched

and drawn into. Lattice, and the Unclear World and Greenhouse

series of holograms are examples of this. I found that the mixture

of media gave me increased scope for yet more socio-political

comment, and at the same time made my work easier to appreciate

for those used to more traditional media.

As a preliminary to my retrospective exhibition Phases at the Museum of Holography New York, in 1980/8, I worked with Stephen Benton at Polaroid to make White Rainbow, which was mine, and Black Rainbow which was his. Stephen Benton is a creative scientist, the inventor of the WLT hologram, who had collaborated previously with Harriet Casdin-Silver and I think I benefited from this fact. I found him extremely intuitive to work with. As a learning experience being able to work with scientists has always been extremely valuable, but creatively, input is rare. White Rainbow was intended as the complement to Rainbow Rainbow. Phases was for me the definitive (and possibly last?) showing of my laser-lit work.

PULSED WORK

Another

significant collaborator for me has been John Webster. In 1981

I returned to the UK and began to work with him at the Central

Electricity Generating Board, making holograms of people with

the pulsed laser he had developed. In Counting the Beats two

exposures a few microseconds apart form dark & light fringes

that give a direct visual readout of our inner & outer body

movements. From the vertical and horizontal directions of the

dark and light fringes you can see that I am shaking my head

in a "no" and he is nodding "yes". Tiresias

is a hologram of both of us occupying the same space, to form

a single androgynous being. The throbbing of the jugular vein

in a necklace pattern round the neck can be seen, and the pulse

of the heart, the traditional seat of the emotions. In 1982 I

set up a studio temporarily, in net curtain territory, in a garage

with a lift-up door. Many artists in the UK work at home, in

a bedroom or garage. In 1983 I moved to a permanent garage studio

which I was able to extend with the help of a Shearwater Award.

I have held teaching courses in this studio, and every couple

of years open it to the public during Dorset Art Week. It is

one of very few artist's holography studios in the world, and

is very modest.

Another

significant collaborator for me has been John Webster. In 1981

I returned to the UK and began to work with him at the Central

Electricity Generating Board, making holograms of people with

the pulsed laser he had developed. In Counting the Beats two

exposures a few microseconds apart form dark & light fringes

that give a direct visual readout of our inner & outer body

movements. From the vertical and horizontal directions of the

dark and light fringes you can see that I am shaking my head

in a "no" and he is nodding "yes". Tiresias

is a hologram of both of us occupying the same space, to form

a single androgynous being. The throbbing of the jugular vein

in a necklace pattern round the neck can be seen, and the pulse

of the heart, the traditional seat of the emotions. In 1982 I

set up a studio temporarily, in net curtain territory, in a garage

with a lift-up door. Many artists in the UK work at home, in

a bedroom or garage. In 1983 I moved to a permanent garage studio

which I was able to extend with the help of a Shearwater Award.

I have held teaching courses in this studio, and every couple

of years open it to the public during Dorset Art Week. It is

one of very few artist's holography studios in the world, and

is very modest.

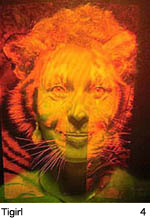

Going back to 1983, more holograms were mastered at the CEGB and transferred in my own studio. The Conjugal Series shows male & female hands carrying out various actions. In modern holography we use the term "master" for the first laser lit hologram that we use to make white-light viewable copies from, rather like the relationship of film to print in photography. I have proposed that we alter the gender-loaded word of "master" to "matrix", because matrix is actually closer to the idea of the mould. In Facial Codes there is more interferometry of the emotions. Tigirl 1985, much to my amazement, became very well-known and liked.

THE COSMETIC SERIES

The

last two projects that I've been involved with are the Cosmetic

Series (5) and Cornucopia. The female Cosmetic Series evolved

out of a self-portrait combining a hologram and an underpainting

carefully registered with the hologram. The painting modifies

the hologram. I decided that I did not want to use myself as

a model, as I had done for many previous pieces, but to generate

myself through younger women, so all the women are around the

age of 23, around the age I felt myself to be inside. The women

were collaborators in the project to make themselves as beautiful

as possible. This was to make us feel as positive about ourselves

as we could.

The

last two projects that I've been involved with are the Cosmetic

Series (5) and Cornucopia. The female Cosmetic Series evolved

out of a self-portrait combining a hologram and an underpainting

carefully registered with the hologram. The painting modifies

the hologram. I decided that I did not want to use myself as

a model, as I had done for many previous pieces, but to generate

myself through younger women, so all the women are around the

age of 23, around the age I felt myself to be inside. The women

were collaborators in the project to make themselves as beautiful

as possible. This was to make us feel as positive about ourselves

as we could.  The

ostensible subject of the Cosmetic Series is the painted face

as a surface or mask. There were technical reasons in pulsed

holography for covering the skin surface with cosmetics, and

I was also frustrated at not being able to retouch the hologram.

There are aspects to some of these works that are holographic

- pre and post-swelling for instance, but there are numbers of

other aspects as well: the relationship with kitsch and identikit

painting. There is a documentary aspect - all the subjects have

their own names apart from Voiles and Black Jack. I thought of

them initially as "heads", like a sculptor, but the

hologram makes them into portraits. None of these people look

like this any more. They are records of people at a single stage

in their lives. Sophie for instance, is sadly no longer alive.

There is also an art-historical aspect, in that figurative paintings

have a relationship with past art. On the ideological plane these

are symbolic representations, in frozen or deep time. They are

static, centralised, hieratic images with neutral expressions.

The

ostensible subject of the Cosmetic Series is the painted face

as a surface or mask. There were technical reasons in pulsed

holography for covering the skin surface with cosmetics, and

I was also frustrated at not being able to retouch the hologram.

There are aspects to some of these works that are holographic

- pre and post-swelling for instance, but there are numbers of

other aspects as well: the relationship with kitsch and identikit

painting. There is a documentary aspect - all the subjects have

their own names apart from Voiles and Black Jack. I thought of

them initially as "heads", like a sculptor, but the

hologram makes them into portraits. None of these people look

like this any more. They are records of people at a single stage

in their lives. Sophie for instance, is sadly no longer alive.

There is also an art-historical aspect, in that figurative paintings

have a relationship with past art. On the ideological plane these

are symbolic representations, in frozen or deep time. They are

static, centralised, hieratic images with neutral expressions.

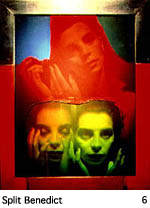

The

work on the master/matrix holograms was done in Paris with Anne

Marie Christakis, who had a pulsed laser, on an exchange basis.

I gave her finished pieces in exchange which she could then hang

in her museum. This work was shown there in 1986 in the exhibition

Mirage Image. During a second session at the Musée the

masters for Benedict Revealed and Split Benedict were made, and

also a start on the male series with Painted Stephan and Drawn

Stephan. This work was shown at ARTEC the international Biennale

in Nagoya, Japan. I felt that there should be a gender balance,

with both genders presented together as equals, but the male

series did not go as planned. The males ended up dominating as

usual. There are currently 12 men to 7 women. The male series

was done at the Royal College of Art as a PHD project (6).

The

work on the master/matrix holograms was done in Paris with Anne

Marie Christakis, who had a pulsed laser, on an exchange basis.

I gave her finished pieces in exchange which she could then hang

in her museum. This work was shown there in 1986 in the exhibition

Mirage Image. During a second session at the Musée the

masters for Benedict Revealed and Split Benedict were made, and

also a start on the male series with Painted Stephan and Drawn

Stephan. This work was shown at ARTEC the international Biennale

in Nagoya, Japan. I felt that there should be a gender balance,

with both genders presented together as equals, but the male

series did not go as planned. The males ended up dominating as

usual. There are currently 12 men to 7 women. The male series

was done at the Royal College of Art as a PHD project (6).

In the male series the psycho-therapeutic

angle changed. In the first two pieces Stephan is made glamorous,

like the women, but I felt that with the males this was the wrong

way to go. In the end the personal angle became not beautification,

but my coming to terms with male authority by using other stereotypes,

such as the soldier, the master artist, and so on. In the male

series I was painting faces in a different way, and hit a number

of problems, one of which was that men didn't have the experience

of "making-up" in  their

everyday lives way that the women had. When I suggested going

back in time, to a time when we were painting our bodies, probably

even before painting the walls of caves, they responded to that,

as in Pagan Paul and Pockel Paul. The male artist/authority figure

for me in the UK was Richard Hamilton. I respected him. He had

always been a technophile. We both got something out of this

collaboration. He showed the piece in his show at the Anthony

D'Offay Gallery. Part of the male series was shown at the Smiths

Gallery by Jonathan Ross but the whole series has not been shown

together yet. (Postscript: Later, in 1998, this work was featured

in "electronically yours" curated by Jasia Reichardt.

This show took place at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography

under the auspices of the National Portrait Gallery, London.)

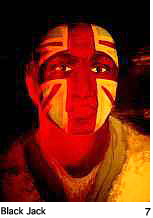

Black Jack is slightly different from the other pieces, in that

the painting that is not related to the hologram in the same

way. The hologram is of a white unemployed Brit with a black

Union Jack painted on his face, and underneath there is a black

man with a coloured Union Jack which shows through the black

Union Jack. It is about social & racial stereotyping. So

is Eddie Coloured.

their

everyday lives way that the women had. When I suggested going

back in time, to a time when we were painting our bodies, probably

even before painting the walls of caves, they responded to that,

as in Pagan Paul and Pockel Paul. The male artist/authority figure

for me in the UK was Richard Hamilton. I respected him. He had

always been a technophile. We both got something out of this

collaboration. He showed the piece in his show at the Anthony

D'Offay Gallery. Part of the male series was shown at the Smiths

Gallery by Jonathan Ross but the whole series has not been shown

together yet. (Postscript: Later, in 1998, this work was featured

in "electronically yours" curated by Jasia Reichardt.

This show took place at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography

under the auspices of the National Portrait Gallery, London.)

Black Jack is slightly different from the other pieces, in that

the painting that is not related to the hologram in the same

way. The hologram is of a white unemployed Brit with a black

Union Jack painted on his face, and underneath there is a black

man with a coloured Union Jack which shows through the black

Union Jack. It is about social & racial stereotyping. So

is Eddie Coloured.

CORNUCOPIA

My solo exhibition Cornucopia at the Russell-Cotes

Museum in Bournemouth during the summer of 1996, showed some

more recent work. It included pieces like the Cornucopia animation

which lent its title to the series, or Rock Garden in which people

found the image by moving around a blue shell spiral. The Cornucopia

animated hologram is computer-morphed between two appropriated

end images to form a virtual object, something that doesn't exist.

The show was about "nature", that is the parts that

were least manipulated by humans. Rock Garden is about a sense

of place, my current habitat on the Dorset coast.

My solo exhibition Cornucopia at the Russell-Cotes

Museum in Bournemouth during the summer of 1996, showed some

more recent work. It included pieces like the Cornucopia animation

which lent its title to the series, or Rock Garden in which people

found the image by moving around a blue shell spiral. The Cornucopia

animated hologram is computer-morphed between two appropriated

end images to form a virtual object, something that doesn't exist.

The show was about "nature", that is the parts that

were least manipulated by humans. Rock Garden is about a sense

of place, my current habitat on the Dorset coast.  Some

aspects of natural abundance are explored, as in Cornucopia Shells,

Cornucopia Concrete in which concrete is made spectral by holography,

and Cornucopia Cauliflower, which is about female fulfilment.

I am interested to see whether this work could be used to define

Some

aspects of natural abundance are explored, as in Cornucopia Shells,

Cornucopia Concrete in which concrete is made spectral by holography,

and Cornucopia Cauliflower, which is about female fulfilment.

I am interested to see whether this work could be used to define

female roles and

characteristics. Such notions as fertility, chaos, lack of rationality,

decoration are often seen negatively as such. In order to understand

and assert women's experiences, many contemporary women artists

have emphasised the importance of and links between, personal

and social political experience. This is important not just for

women but for the field as a whole.

female roles and

characteristics. Such notions as fertility, chaos, lack of rationality,

decoration are often seen negatively as such. In order to understand

and assert women's experiences, many contemporary women artists

have emphasised the importance of and links between, personal

and social political experience. This is important not just for

women but for the field as a whole.

Other pieces in the show were Wrapped Flowers,

Enough Tyranny and the Enough Tyranny Travel Pack. An image of

binding together, Web, was combined with a hologram entitled

Blue, to make Web Blue Web. I have made a number of pieces with

the theme of web or binding. There have been cyclic, constant

themes that have persisted throughout my life. Many artists are

working from their life experience, one might even say "inner

life" experience. The themes or triggers are constant, but

the way they are presented differs with time. Curtain comes into

this same category. The curtain is closed, but it is planned

to be combined in future with a curtain opening onto blue, an

image of revelation. The only piece in the show which involved

a human being was "Pushing up the Daisies". It is an

epitaph, and an epitaph to this paper.

Other pieces in the show were Wrapped Flowers,

Enough Tyranny and the Enough Tyranny Travel Pack. An image of

binding together, Web, was combined with a hologram entitled

Blue, to make Web Blue Web. I have made a number of pieces with

the theme of web or binding. There have been cyclic, constant

themes that have persisted throughout my life. Many artists are

working from their life experience, one might even say "inner

life" experience. The themes or triggers are constant, but

the way they are presented differs with time. Curtain comes into

this same category. The curtain is closed, but it is planned

to be combined in future with a curtain opening onto blue, an

image of revelation. The only piece in the show which involved

a human being was "Pushing up the Daisies". It is an

epitaph, and an epitaph to this paper.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people and organisations have assisted and collaborated with me through the years, and I would like to take this opportunity to thank them all. On this occasion I would like thank Andy Pepper, the organiser of this symposium, and above all Posy Jackson, who founded the Museum of Holography New York in 1976. The number of artists using holography world-wide is still very small - at a generous estimate about 300 - and Posy has played a part in many of their lives.

NOTES and REFERENCES

1 "Any dispute as to whether Benyon is an important artist is premature, since her work in a completely unexplored medium is defining its own criteria." Science and Technology In Art Today. Jonathon Benthall. Thames and Hudson. pp 89 -93. 1972

2 1973 'Holography as an Art Medium.' Leonardo. Vol 6, No 1, pp 1 - 9 was re-printed in Kinetic Art: Theory and Practice. Dover. pp. 185 - 192. 1974.

3 Apparition. Holographic Art in Australia. Rebecca Coyle & Phillip Hayward. Power Publications, Sydney. Ch 2 "Margaret Benyon: The Founding of Holographic Art", pp 23 - 37. 1995

4 This was featured in the Creative Holography Index, the International Catalogue for Holography. Vol 1, Issue 1. Editor, Andrew Pepper. Monand Press, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany. 1993.

5 Art of the Electronic Age. Frank Popper. Thames and Hudson, pp 38 - 39. 1993

6 My PhD thesis How is Holography Art? is accessible through the British Library, Fax 0937 546286, quoting shelf No: DX 179873, and the Royal College of Art Library, London. 40,000 words. 1994.

ON-LINE REFERENCES

The Benyon Archive is the main on-line

source for information about my work

(see www.mbenyon.com ). This developed from the text and pictures on the HoloNet site (see www.holonet.khm.de ).

Some entries on my work can be found in the collection, exhibition and stereo sections of Jonathan Ross's website (see www.jrholocollection.com )

The Artists Database on the ICC site includes some work and a biography in the alphabetical index (see www.ntticc.or.jp) as does the G.R.A.M site, which also includes some text in the commentary and reference sections (see www.comm.uqam.ca/~GRAM/#pseudotarget.htm).

My work in the travelling exhibition Unfolding Light curated by Rene Barilleaux, can be seen on the MIT Museum site (see web.mit.edu/museum/exhibits/artist2.html) .

Also, an interview with Al Razutis from Wavefront Magazine, Fall 1986, can be found on Al's site (see www.holonet.khm.de/visual_alchemy/wavefront/wave13.html)

Images

| 1 | Hot

Air 1970 8" x 10" laser transmission hologram. Collection: Australian National Gallery. |

| 2 | Solar

Markers 1979 Reflection holograms approx. 1.5" x 1" mounted on rocks. Collection: MIT Museum, Boston |

| 3 | Tiresias 1981 In collaboration with John Webster 12" x 16" white light transmission hologram Collections: MIT Museum, Boston, USA. Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

| 4 | Tigirl 1985 33 x 30cm reflection hologram and reproduction Collections: MIT Museum Boston, USA; Museum für Holographie und Neue Visuelle Medien, Germany; and the Jonathan Ross Collection. |

| 6 | Sophie 1986 40 x 30cm reflection hologram & laser colour copy Collection: Musée de L'Holographie, Paris |

| 7 | Split

Benedict 1989 40 x 30cm collage of reduced image reflection holograms Collection: Musée de L'Holographie, Paris. Jonathan Ross Collection. |

| 8 | Black

Jack 1993 43 x 32 reflection hologram & laser colour copy Collection: Sanjou Laser Co, Beijing, China. |

| 9 | Cornucopia

Shells 1993 50 x 60cm open aperture transmission hologram & collaged film on acetate |

| 10 | Cornucopia

CauliFlower 1993 50 x 60cm open aperture transmission hologram |

| 11 | Curtain 1993 50 x 60cm reflection hologram |

| 12 | Cornucopia 1994/6 8" x 10" holographic stereogram. Computer morphed animation. Collection: Jonathan Ross Collection. |